AN ARCHIVE OF ORIGINAL LETTERS FROM KURT VONNEGUT TO ROBERT POINDEXTER PACE, COMPLETE WITH THEIR ORIGINAL STAMPED, ADDRESSED ENVELOPES. A previously unpublished cache of nineteen substantial letters (dated 1974-2001) from the novelist Kurt Vonnegut (1922-2007) to his old colleague and friend Robert Poindexter Pace (1920-2019).

"Penthouse is working on an article about things people think are better than fucking. They asked me, and I told them about eating frozen blueberries from wild bushes in northern Finland. They were like sherbert, and better than fucking anyday." (Letter, January 5, 1978) "Here it is Christmas eve again, and I have failed again to persuade a wife that Jesus was born tonight and not tomorrow morning […] I ask them: Were the Wise Men wearing pajamas and rubbing sleepers out of their eyes and waiting for the coffee to perk?" (Letter, December 24, 1987) "I find it painful to read the in-depth truths about my friend John Cheever. I would rather not know. As my life nears its end, I suppose I could write a sort of Movable Feast, but that would be like Captain Kangaroo's suddenly turning into a rattlesnake." (Letter, November 25, 1991) "Thank goodness you and Ollie and Phil are still around. Practically everybody I ever cared about is dead now. I never expected to put my own generation to bed. Now the funerals I go to are for their children." (Letter, March 2, 1999)

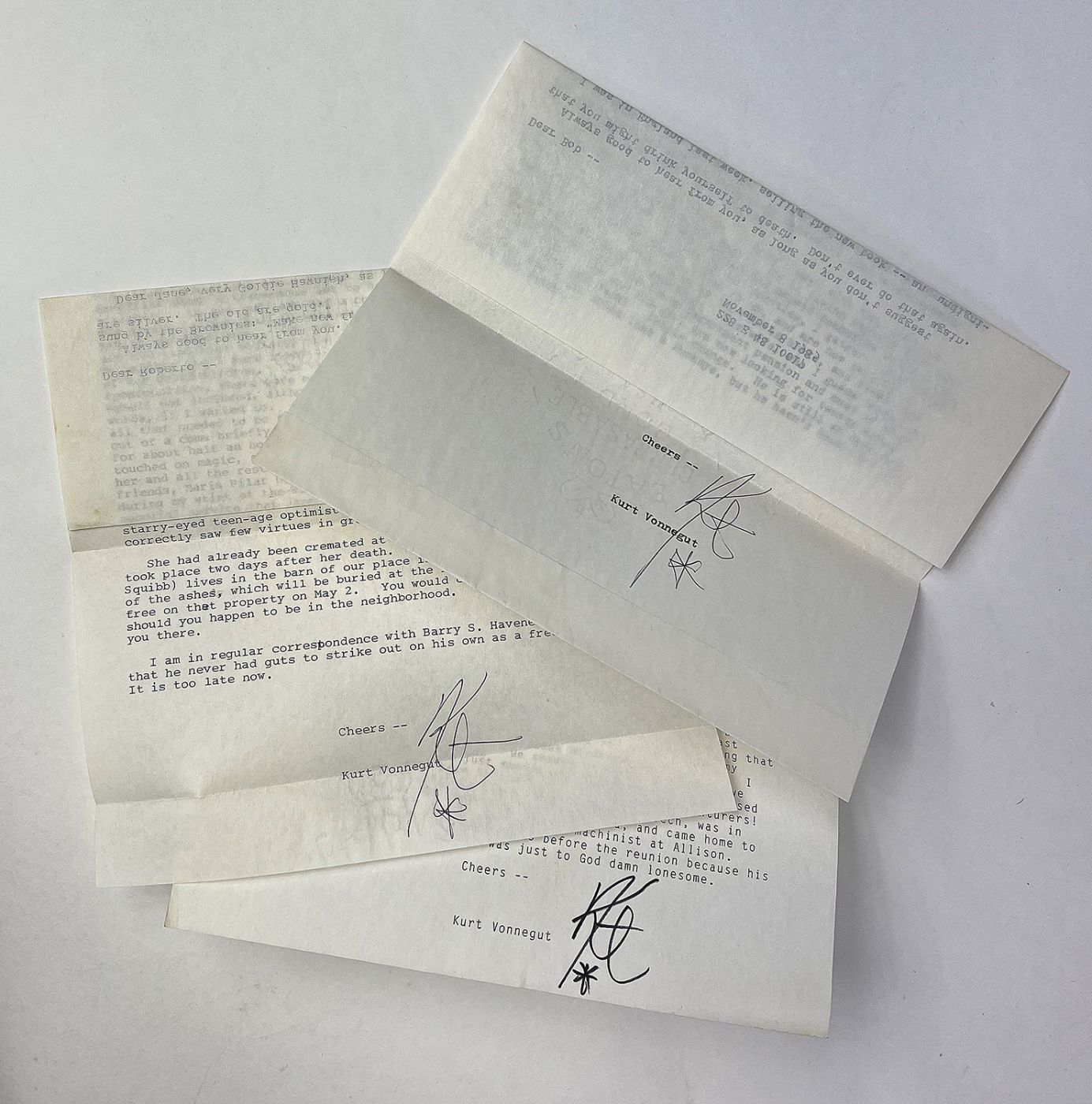

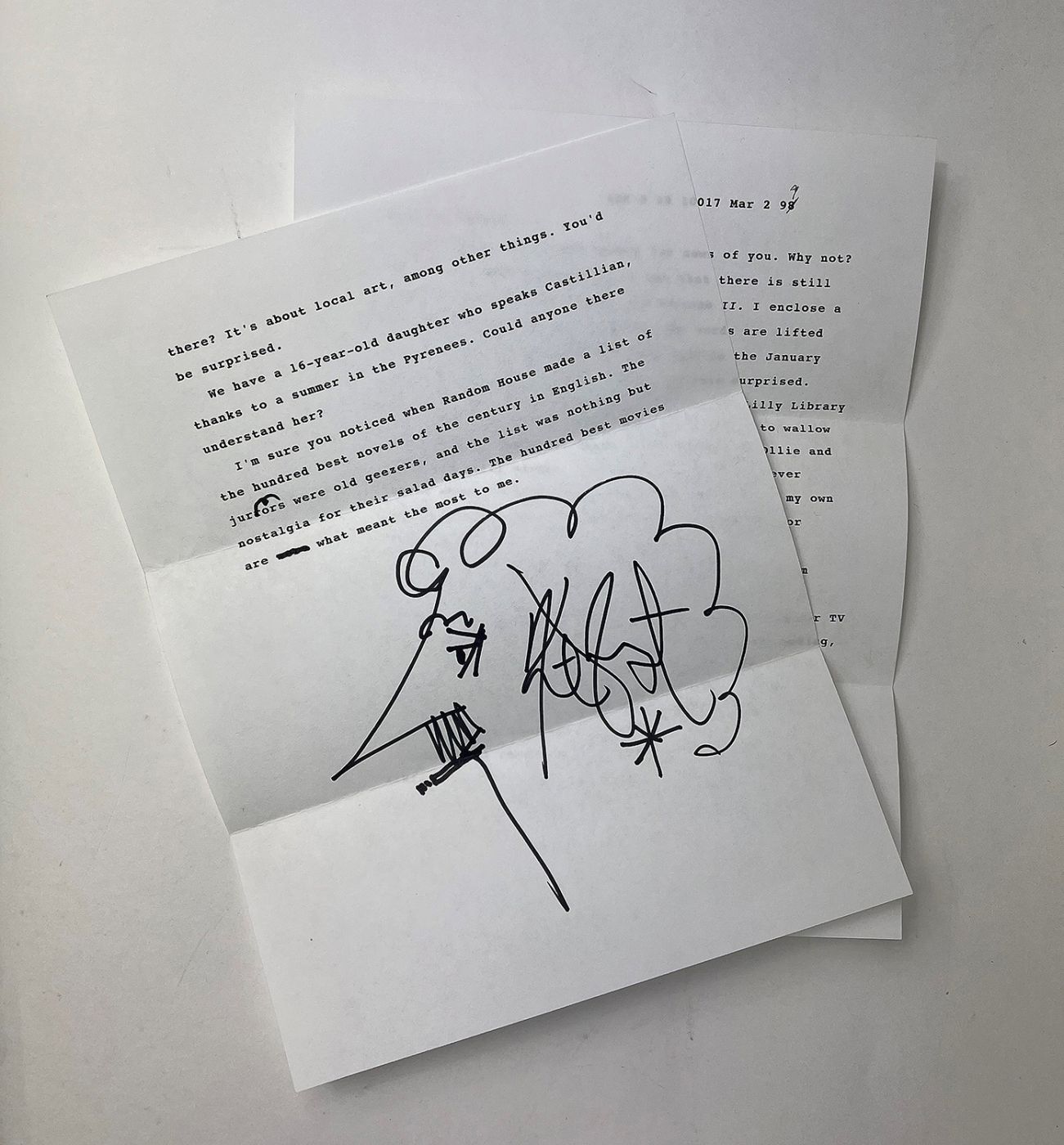

Kurt Vonnegut and Robert Poindexter Pace both grew up in Indiana, attending the same High School (two years apart), and later serving in the military during World War II (Vonnegut's experiences in Europe were later quarried for Slaughterhouse-Five (1969)). The two men didn't meet, however, until after the war when they both found themselves working in the offices of General Electric in Schenectady, New York. Vonnegut, after a spell at the University of Chicago on the G.I. Bill (having previously withdrawn from Cornell for military service), was employed as a technical writer and publicist, obtaining the job with the help of his older brother, Bernard, already at GE. He liked the job, and a handful of the men he worked with during these years, chiefly Pace, became lifelong friends. In his biography of Vonnegut, Charles Shields remarks that he was fond of the "maleness" and "camaraderie" of the office, and these letters to Pace are correspondingly unrestrained. Vonnegut clearly loves his old friend and feels able to write anything, however rude, personal, or solemn. The particular bond with Pace may owe something to their shared background (in one letter, Vonnegut addresses Pace as his "Dear old Hoosier buddy, dear Bob"; Hoosier, a demonym for the people of Indiana), allowing Vonnegut to reminisce freely about his father (for example), an architect whose buildings in Indiana were familiar to Pace. In June 1976, responding to a newspaper cutting sent by Pace reporting that the architect Evens Woolen was living in Vonnegut Sr's self-designed house, Vonnegut writes: "It is sweet to me that [Woolen] lives in the best thing my father was ever allowed to do, his own home. My old man never had a client who would let him express anything he himself believed. He was bitter at the end, and even toward the middle, come to think of it. Hi ho." In 1994, he returns to the subject (and the house): "Yours of March 29 discovered me returning from a visit to Indianapolis and Culver, both of which have been neutron bombed. The buildings still stood, but the people were gone. The most interesting building my father ever designed, our house at 44th and Illinois, to which I bade farewell when I was 10, is a frequent stop on house tours now. It still has my parents' monograms in the leaded glass window in the front door. My daughter Nanny Prior, now 39, was with me. She cried when she saw the monograms. I didn't … I may have become a sociopath." ~ Failing health is a running theme (always, however, animated by Vonnegut's wit). The earliest, and shortest, letter here, dated January 23 1974, refers to Pace's recent back injury ("That's horrible news about your back"), and encourages his friend to keep in touch ("I would love to hear from you often, have Jill [Vonnegut's partner, and later wife] feed you from time to time, and help you to get a big money job, if you want one."). Pace seems to have had intermittent problems with alcohol. In October 1974, Vonnegut remarks that "[t]he business about not smoking or drinking worries me. I take a dim view of steam engines without safety valves", but by 1978 he is starting to worry about his friend, "since you hadn't written for so long. It's good to hear you're O.K., if vaguely sozzled now and then". By November 1985, it is "[a]lways good to hear from you, as long as you don't suggest that you might drink yourself to death. Don't ever do that again." The letters, like the novels, are haunted by death. Ollie Lyon, a GE alumnus and fellow friend is, in June 1976, a "new widower [:] a lonesome, beautiful guy, with no wife any more and his two kids gone". The following December Vonnegut picks up the story, "I assume you know that Ollie's son Phil was killed in a motorcycle accident a couple of months ago. […] He seemed so horribly hoodooed that I couldn't think of anything to say to him for a while". "[S]o life goes on", he concludes (echoing Slaughterhouse-Five's refrain, "so it goes"); "I am always amazed by how it goes on and on. I often think people are too good for life." In 1987 (Christmas Eve), he writes of a school reunion ("School 43, the James Whitcomb Riley School"): "We showed no interest in what we had become. We just mooned and marveled at what we used to be. What keen little kids! What brave adventurers!", before relating that his "best pal" at the school, Bob Forslund, who served "in the Navy at the Battle of the coral Sea, and came home to flunk out of Butler and become a machinist at Allison", had "commited suicide two weeks before the reunion because his wife had died, and he was just to [sic] damn lonesome." "The trip into the Afterlife" he writes (September 1, 2000), after being unconscious for three days following a fire at his New York home ("a most agreeable near-death experience"), "is not a blue tunnel, as so many have reported, but a waiting passenger train, all lit up inside." ~ The letters are equally frank about matters of love and family. "Jill [Krementz, photographer and author] and I remain together after nine years", he writes (September 17, 1979), "and more happily than ever. We bought a summer house in Sagaponack, and she paid half. I liked that a lot, her paying half." Later the same year Vonnegut's divorce from his first wife Jane was finalised (after thirty-four years of marriage), and although he and Jill never intended to marry, they tied the knot in November. When his first wife, Jane, dies of cancer in 1986, Vonnegut is clearly distraught. He later wrote movingly of her life and death in the collection, Fates Worse Than Death (1991), but the letter he writes to Pace the following February (1987), with its characteristic mix of solemnity and wit, is a richer account than the one given in the memoir, or indeed the published letters concerning Jane's death. As with his father, so with his ex-wife, Pace (who knew Jane well) was Vonnegut's ideal interlocutor. In 1991 (November 25), encouraging Pace to write about himself, he adds "write about dear Jane as well. That subject is and always will be too painful for me to write about. I became for her one kid too many." ~ Vonnegut's self-lacerating attitude to his own writing is also ever-present. On Boxing Day, 1974, he notes "I have only just now gotten a book [that became Slapstick, 1976] moving to my own satisfaction. The process is interminable, like making wallpaper by hand for the Metropolitan Opera House." In January 1978, he is "writing another book [Jailbird, 1979], not knowing what else to do with my life. I think each book will be slightly worse than the last one from now on. What the hell." Of Hocus Pocus (1990), "the end", he writes (January 6, 1990), "except for getting the manuscript back from my editor with more flags than the Spanish Armada, is maybe only a month away. That is the orgasm, of course, finishing a motherfucker and handing it to somebody else, saying, "Here, it's yours now. I never want to see it again."" In November 1995, "people are much sweeter to me now, since I no longer publish. I have become a Caucasian Ralph Ellison. Many others of our generation are still in full cry, and I wish they weren't. It's all such crap, which is what I'm writing, too, day after day. But I have the decency not to publish it." Timequake, however, Vonnegut's labyrinthine auto-fiction, emerged in 1997. He is still "noodl[ing] every morning on the keys of my computer", in September of 2000, "wondering if I might not have yet another novel in me, as old as I am. But I remember what such gallantry has done to the reputations of Hemingway and Heller and Bellow, who wrote such junk books at the end. Mine would be even worse than theirs, you can bet your ass." Beginning with "Dear Bob", "Dear Poindexter", or "Dear Roberto", the letters are signed off with "Cheers", "Ole!", "Much Love, old pal" and, in the three final letters, with Vonnegut's wonderful self-portrait caricature of his face in profile. Funny, sad, and always entertaining, these letters are a snapshot of a great writer – and great letter writer – at the height of his powers. References: Charles J. Shields, And So it Goes: Kurt Vonnegut: A Life (New York: Henry Holt, 2011) Kurt Vonnegut: Letters, ed. Dan Wakefield (New York: Delacorte Press, 2012) Robert Poindexter Pace Collection, Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/afc2001001.65392.ph0001001/?sp=1&st=gallery

Stock code: 22918

£14,500

Published:

Original manuscript.

1974

Category

Modern First EditionsSigned / Inscribed

Literature

Manuscripts