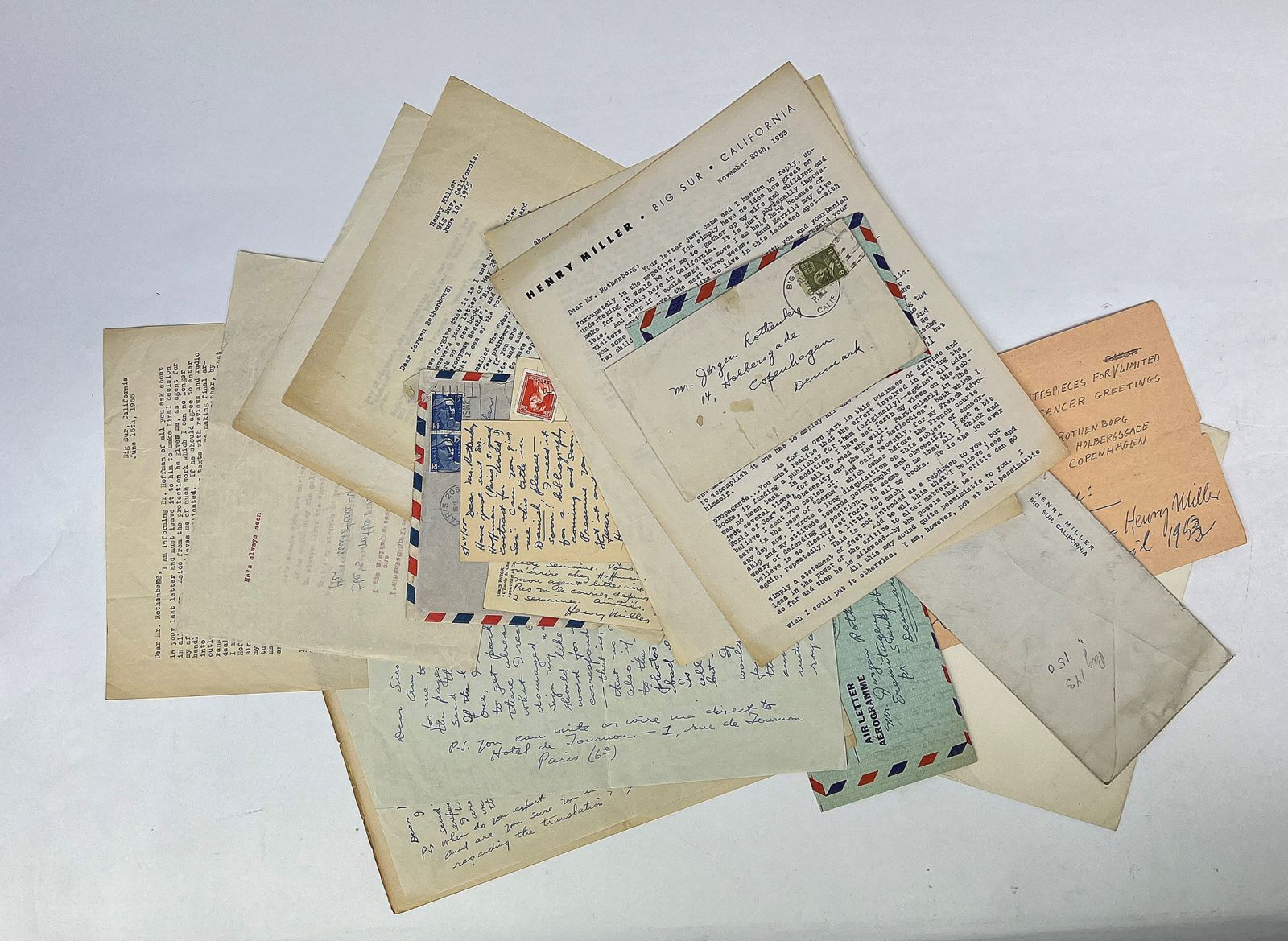

A COLLECTION OF AUTOGRAPH AND TYPED LETTERS SIGNED, FROM MILLER TO HIS DANISH TRANSLATOR, JØRGEN ROTHENBORG, INCLUDING A TYPED, HAND-CORRECTED DRAFT OF AN UNPUBLISHED COMIC POEM, AND A LETTER FROM EVE MILLER (McCLURE).

Six autograph letters signed, two autograph postcards signed, three typed letters signed, one typed poem with emendations; one typed letter signed from Eve Miller; one telegram from Henry Miller to Rothenborg with notes by the recipient. "Please do not think that I am unappreciative of all you are doing for me. I know you have done much more than merely translate my work. Things move slowly in your part of the world, and to rouse the Danes (and the Dutch and the Norwegians, to say nothing of the Swedes) to fever pitch about my work is a task I envy no man. To make haste slowly seems like a wise adage" (Letter, June 15th, 1955) "To answer [your] question – "stink-finger" means to put your fingers in a woman's vagina – hence the "stink". […] PS […] are you sure you have no other questions to put me regarding the translation? I am at your service." (Letter, April 4th, 1953) A previously unpublished series of letters and postcards (including a telegram and a draft of a comic poem) from the novelist, Henry Miller (1891-1980), to his Danish translator, Jørgen Rothenborg. The letters provide a fascinating insight into the many obstacles Miller encountered in publishing his novels: practical problems of transatlantic, multilingual communication, and the perennial problem of censorship. They show the author's care regarding fine details of publication (even in a language he couldn't read) and the sane, patient attitude to the continued international suppression of his novels. For much of his writing life, Miller was better known for the (alleged) obscenity of his novels than for the writing itself. He was in his forties before Tropic of Cancer, his first and still most famous novel, appeared in 1934 (having failed to find a publisher for the earlier Crazy Cock, eventually published in 1991). The novel, funded by the young Anaïs Nin was singled out for praise by T. S. Eliot ("a... magnificent piece of work"), Ezra Pound (who mentioned it in the same breath as Ulysses), Beckett ("a momentous event in the history of modern writing"), to name just three of its illustrious admirers. Critical acclaim, though, however gratifying, wouldn't pay the bills.� Although the series of trials initiated by Barney Rosset's 1961 Grove Press publication of Cancer would soon lead to Miller's novels becoming widely available, in the 1950s (when these letters to his Danish translator were written) Miller was seemingly resigned to the continued suppression of his works.

The correspondence begins with a telegram (on the pink Danske Statstelegraf card) instructing Rothenborg to contact Miller via his agent, Dr. Hofmann, in Paris. This will become a familiar refrain, the busy novelist trying, always courteously, to steer his enthusiastic correspondent into a more formal, professional relationship. The verso of the card includes a pencilled enquiry (in Rothenborg's hand) asking the author if he will sign 750 frontispieces for a forthcoming limited edition of the translation of Tropic of Cancer, underneath which Miller has written "telegramme reçu: / Un peu perplexe = Henry Miller; and (later) "letter suitant le 6 avril 1953"). The earliest letter here (Paris, 5th March, 1953, though the cancellation of the envelope gives 4th April, suggesting it to be the letter referred to on the verso of the telegram), in the author's loose but always legible hand, strikes the tone of mild, though courteous, impatience that will characterise the correspondence. Miller is "not sure whether you meant for me to come to Copenhagen [he cannot afford to pay for a flight to Copenhagen himself "until I touch more French royalties"] to sign the pages or whether you wished to send them to me here in Paris". The latter will involve wasting valuable time queueing at the customs office ("I loathe going to the Douane to get packages – have wasted hours there already. And no matter what I receive it arrives in a damaged condition"). He requests information about the accuracy of the translation, and regarding the proposed illustrations (asking for photos), "Excuse my bluntness, but it is quite important to me". The next letter continues the saga of the frontispiece pages, Miller now suggesting they be sent to Brussels, where he will be stationed for a week in April. (This clearly didn't happen, but the next message, in the form of a postcard showing – a nice touch – James Ensor's "L'Entrée du Christ à Bruxelles" is from Bruges and apologises, in French, for having forgotten to do something when in Brussels.) By November 20th, when the correspondence resumes, Miller is back in Big Sur, California (his home since 1944), and back with his typewriter. Rothenborg, it seems, has asked Miller to travel to a California studio to make a recording. "You simply have no idea how great an undertaking it would be for me to gather up my wife and children and make for a studio […]. It is physically impossible. Knud Merrild [the artist and friend of both correspondents] may give you some idea of what it is like to live in this isolated spot—with two children aged 5 and 8!" (the two children were from his marriage to Janina Martha Lepska; by this time he was married to Eve McClure). Keen to show his gratitude to Rothenborg and his "Danish compatriots […] so eager to be of service to me" ("I regard your motives as perfectly pure—unquestionably"), he is equally keen to keep things in perspective, "If I may say so, without wounding you, I think perhaps you are exaggerating the importance of this event: the publication of Cancer in Danish". The letter includes a measured and sane statement of his attitude to the continued suppression of his work: "My frank opinion is that my banned books will never be free to circulate in this country, or England. Meanwhile, however, these books are gradually being translated and published in other countries of the world. Whether Denmark follows suit depends upon the Danish public. The law, however absurd or unjust, does in great measure respond to the needs or desires—or prejudices, if you like—of the people who make them. To butt one's head against a stone wall is futile". Steering Rothenborg towards his existing statements on such matters, "[p]articularly […] The World of Sex and "Obscenity and the Law of Reflection", he confesses to being "a bit weary of defending my position". Even so, Miller by now has clearly warmed to Rothenborg: "I would venture to add, as a final word, my dear friend, that if my book has been an aid and an inspiration to you, just you alone, that is a great deal—perhaps enough". By August of 1954 (Big Sur, handwritten), Miller has three copies of the Danish Cancer ("please accept my thanks. I like the format. Wish I knew Danish!"), asking a number of questions (is it limited, where is the date printed, which is the name of the publisher and which the printer?) and (as if this was inevitable) if "you have had had any trouble yet with the authorities?" In May 1955, mentioning the recent suppression of Sexus in Japan, Miller adds, "[I t]hink you would have still more trouble in Denmark. Think it over!"; and in June, broaching the matter of Sexus again, he advises Rothenborg to "think twice—or three times—before spending your energies on the translation […]. If the two most liberal countries in the world (liberal with regard to matters of sex, at any rate), have suppressed this book, what chance have you with the Danes?". He would have more chance with either Plexus ("one of the books I like best of all I have written"), his book on Rimbaud, or The Colossus of Maroussi, "which the Danes would probably like" (a book, as Miller's biographer Jay Martin notes, "wholly without sex, a celebration of the grace and wisdom of the Greek spirit"). In June, Miller's wife Eve writes to Rothenborg on her husband's behalf ("He is hard at work on a new book, Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymous Bosch, and I will attempt to take over what I can of the correspondence"). Eve, like Miller, is keen to persuade the avid translator to deal with Dr. Hoffman ("Mr. Miller approves fully of everything that Dr. Hoffman does in his behalf"). Within a week, however, Henry is writing again, and again advising him to deal with Hoffman ("Whatever difficulties you may be encountering can be straightened out if you simply speak frankly and honestly with him—and trust him"). Among the letters is a draft of an unpublished piece of comic verse, typed in red ink, and with corrections and additions in Miller's hand. It is unclear whether it is a single page from a longer work, and what connection (if any) it has to Rothenborg. The poem, in three quatrains each ending with the refrain, "That's my stepson to you" (and a couple of stray couplets) ends with the lines, "I'v[e] hunted up I've hunted down to start a family / I got one wife, a second too – and now a number three". By the time of these letters, though, Miller was already on wife number four with another to follow (and he didn't have a stepson).

Stock code: 23033

£4,500

Published:

Original Manuscript.

1953

Category

Modern First EditionsSigned / Inscribed

Literature

Non-fiction

Manuscripts